Should Platforms Remain Immune From Enabling Bad Acts?

France's arrest of Telegram’s founder has re-ignited debate over how much responsibility platforms should hold for vile acts on their technology.

The arrest last week of Telegram founder Pavel Durov by French prosecutors set off a firestorm of controversy. A tech founder who fled Russia when he didn’t want to kowtow to Vladimir Putin’s demands for government manipulation of his social media platform, Durov instead found the inside of a cell in a Western liberal democracy for the same act.

The French allege he’s not cooperating with an investigation into child sexual assault material (CSAM) on his platform. Durov’s position for Telegram has been that he is simply upholding the principle of free speech on his platform regardless of the content. In any event, it brings up a lot of uncomfortable questions about what we allow on these platforms - and why.

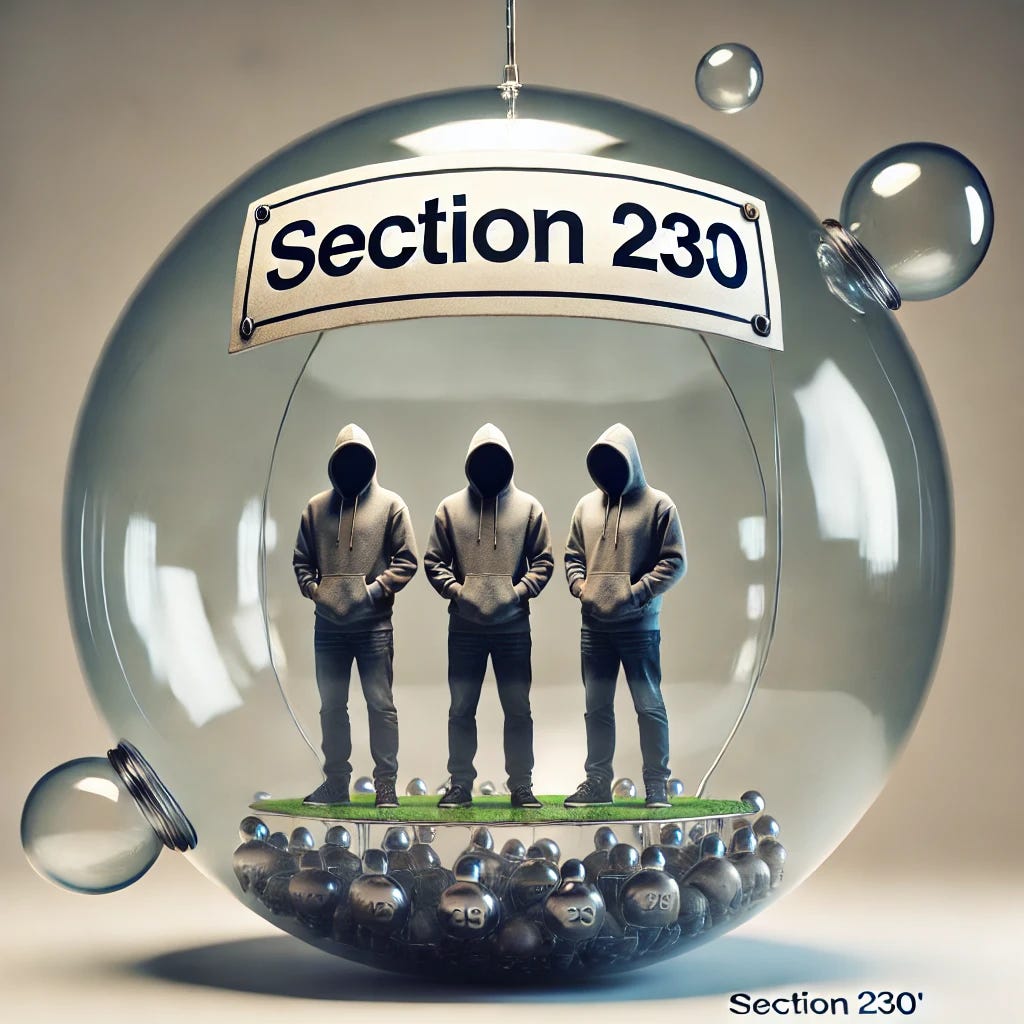

Section 230 Set The Stage

If we go way back to 1996 when the internet was in a very nascent stage, there was legitimate concern that any efforts to hold accountable major platform providers for the content they enabled on their services would stifle free expression and innovation on the new-fangled world wide web. This led to the addition of legislation tacked onto a decades-old law called the Communications Act of 1934.

Section 230 of this addition (formally called the Communications Decency Act of 1996) has two crucial subsections - (c)(1) and (c)(2). Section 1 provides immunity for platform owners, saying they are not the publishers of someone else’s content. In other words, if I threaten someone’s life on Meta, Meta cannot be held liable for enabling the threat because they didn’t actually create it themselves.

Section 2 goes further and provides civil immunity as long as the platform is conducting “good faith” removal of such problematic material. So the person whose life I threatened in the earlier hypothetical can’t go after the billions that the platform generates on content it enables (but, crucially, does not “create”) but can only go after the person generating the problematic content.

Despite having gone to law school orientation and cutting an admissions check to a New York area law school, this newsletter’s author is not a lawyer, but even he can see the ambiguity written into the law meant to tip towards platforms. Keep in mind, the law was written in response to lawsuits popping up against mid-1990s internet forums for the kind of content being published on them. The idea of social media as we know it today wasn’t quite formed in the consumer’s consciousness; Friendster - often pointed to as the first iteration of modern online social networks - was not invented until 2002. MySpace, which was most millennials’ foray into social media (including this author’s) was not a thing until 2003.

Interestingly, Section 230 had to be separated from the rest of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, as the Supreme Court found the rest of the legislation ran afoul of a little thing called the Constitution. Section 230 has been challenged - and upheld - numerous times. So for now, it’s here to stay.

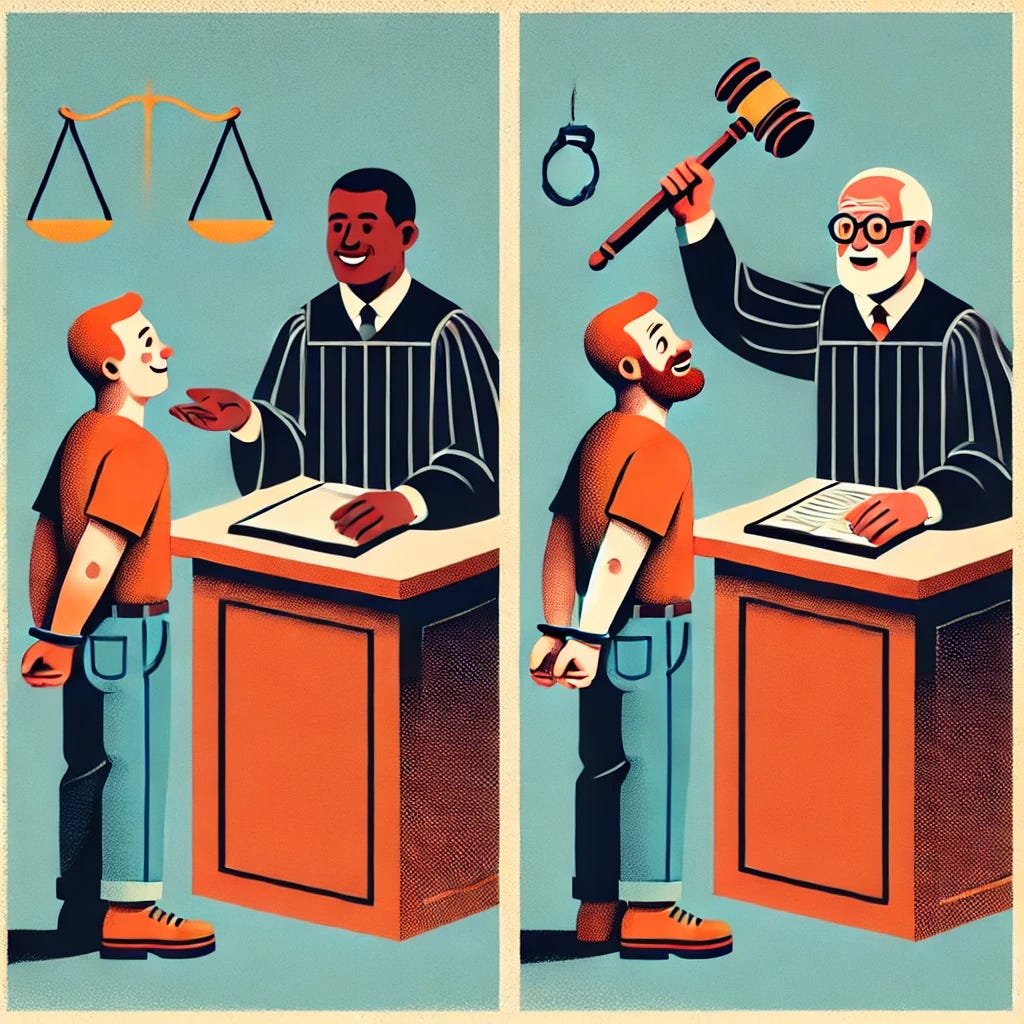

Are We Seeing a Double Standard Emerge?

While Section 230 is an American law, the kinds of platforms that tend to dominate the internet are American companies and there is undoubtedly an American skew - if not at least a Western liberal values lens - to how much of the globe approaches the internet as most of us know it today (that is, through logging on from Western liberal states.)

Which makes France’s arrest of Telegram founder Pavel Durov that much more complex when it comes to the enablement of the kind of content that any decent person agrees is vile and should be wiped off of the face of the Earth.

French prosecutors (and judges, as their legal system is a little different when it comes to these kinds of investigations) aren’t pointing to the content itself as the reason for Durov’s arrest. The founder’s mistake was not in allowing that kind of content on his platform, but in not cooperating with authorities when they wanted the identity of the bad actors using Telegram for disgusting CSAM purposes.

Which brings up the first uncomfortable question: If tech executives like Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg or X’s Elon Musk allow this kind of material on their platforms, but cooperate with authorities when asked, should they be free of liability and responsibility for it? Section 230 - and European prosecutors up until last Thursday - say yes. But is that the approach we as a society should be taking?

If we know this kind of material proliferates on these platforms - in part thanks to black-box algorithms that actually accelerate its spread - why are we as a society allowing the platforms to exist with no accountability of their owners? Merely because they respond when law enforcement asks for information on a small number of those cases?

The line for platform responsibility should not be platform owner response, but the mere existence of harmful material. It is the act of enabling this kind of material that should trigger some kind of responsibility, not cooperation around it or volume of it.

The Cost of Doing Business?

The argument could very easily be made that while bad actors and horrific acts will always be prevalent on platforms like Telegram, Meta, and X, it should not preclude those platforms from existing. After all, there is plenty good that comes from these platforms. While true, this is a dangerous line of thought in this newsletter’s humble opinion.

The same argument is made in gun regulation arguments: sure, firearms are now the leading cause of death for children and teens in America, but that sacrifice - the literal blood of children - does not rise to the level necessary to further regulate American guns. In other words, it’s a valid sacrifice as our elected officials see it. Thus, we find ourselves in the situation we are when it comes to firearms in America - one so wildly out of step with the rest of the world that they see the mass shootings we’re all at risk of every day as a feature of the system, not a bug.

And so it goes with the harm social media brings in the way of vile CSAM content distribution. We have to ask ourselves - is maintaining legislation like Section 230 worth the collateral damage of child exploitation? Is ensuring billionaires like Zuck and Musk aren’t held accountable for the type of actions their platforms enable worth the “innovation” Section 230 allegedly catalyzes?

This newsletter does not subscribe to the collateral damage argument. As long as there is one piece of CSAM material being distributed on these platforms someone on the platform side needs to be held accountable. Do they need to be arrested like Durov? We can argue nuance here, as heavy, EU-level fines would go a long way towards funding the fight against CSAM, a fight criminally underfunded especially as the advent of artificial intelligence leads to an explosion of the material on the web and these platforms.

Too Complex for Simple Answers

So what are the answers to these uncomfortable questions? That’s the rub - there are no right and definitive answers to them. We can all agree that CSAM should be wiped out, but from there it becomes a question of who is responsible and how. Section 230 is a massive roadblock to that, at least within the States. France’s move against Telegram’s Durov should bring these questions to the forefront of a debate that has bubbled under the surface behind larger electoral issues in the US. It might very well be time to have the Section 230 debate once and for all.

Grab Bag Sections

WTF MRIs: This newsletter’s author has found himself lucky enough to get an MRI for potential hand surgery (don’t get old, kids.) I’ve had MRIs before, so didn’t stress it too much, but I was surprised on the protocol for this kind of MRI when I got there.

The way the MRI was done for imaging the top of a wrist was crazy. I had to lay on my stomach, with my arm outstretched in front of me for the 20 minutes or so as the machine digitally chopped up my arm. Can we not make one for external limbs that doesn’t require this kind of yoga-esque contortionism? Maybe like one of those blood pressure machines at the pharmacy?

And can we talk about the noise? The noise! They asked me what kind of music I wanted - I could barely hear Mos Def’s mumbled voice over the sound of whatever the hell is happening in that little tube. Just like flying, we’ve taken an incredible technology and made it as miserable as possible for the consumer.

Album of the Week: Boldly not giving a fuck, the trio from Belfast named Kneecap (named after the infamous IRA punishment for turning tout) is ruffling many a feather across the pond and reveling in every aspect of it.

Fine Art is part of a resurgence of the Irish language seen in recent media, thanks to the popularity of actors like Cillian Murphy and Barry Keoghan seemingly opening up a portal into wider Irish media. It's a refreshing trend, as the Gaeltacht continues to decline it needs to be buttressed by what is called the "urban Irish" speakers. For a language that has faced ban after ban since the 14th century - and never received legal recognition in Northern Ireland until 2006 - it is an incredible cultural survival.

Taking off my hat as a gaotaire m crosbhealaigh, let's look at the album itself. It starts off with a hauntingly beautiful melody in “3CAG”, even if the name and Irish lyrics behind it aren’t particularly stunning. “Fine Art” is the group’s reflection on their newfound fame and the external expectations that come with it. You can hear the grime influence most in “Drug Dealing Pagans.” “Parful” is a very clubb-y banger. Not this newsletter's cuppa, but a good song nonetheless (especially if you're into that kind of thing.) The outro in "Way Too Much" is an excellent way to end the album and might be the best song on it.

Take a listen - it’s likely a departure from your usual listening rotation, but variety is the spice of life.

Quote of the Week: “Children are the world’s most valuable resource and its best hope for the future.” - John F. Kennedy

See you next week!