Net Neutrality Is Dead

An incoming anti-net neutrality administration, recent overturning of decades-long legal precedence, and a family-owned fishery have all played a role in the downfall of a free and open internet.

You may be forgiven for missing it between terror attacks on Bourbon Street and Teslas blowing up on purpose, but the set of rules collectively known as net neutrality were struck down by a federal appeals court Thursday of last week. It was a whimper of a finale for a regulatory framework debate that was so impassioned at the beginning of its outset almost 20 years ago.

This doesn’t mean that net neutrality is dead forever, but it does mean that for it to be enacted in the US, Congress is going to have it get its act together. So for the time being, net neutrality is dead. That is a bad thing for those who like to choose what they browse on the internet, as it allows de facto gatekeeping of content by your internet service provider who - it may shock you to find out - does not always have the consumer’s best interest at heart.

History of Net Neutrality

Net neutrality as a theory has roots in the Clinton Administration, who helped usher in the deregulation of the telco industry in regards to the Internet with the Telecommunications Act of 1996. It’s seen by some as the linchpin to increasing high-speed access to the internet while others point to it as the death knell of public access to alternative media as it allowed already-dominant companies to expand their power into the burgeoning ISP market - something that would have been disallowed by the Ma Bell ruling of 1982, which this act did much to undo (quick shoutout to NYNEX.)

The act also contains the infamous Section 230 under the since-gutted Communications Decency Act portion of the legislation. The passage of the Telecommunications Act brought questions of whether broadband should be subjected to common carrier rules, given its importance to the public as a whole, which is where the net neutrality piece often comes in. But we’re digressing.

The actual term “network neutrality” is often attributed to Tim Wu (of anti-trust discussion fame on this newsletter) in a 2003 article in the Journal on Telecom and High Tech Law. If you’re not a subscriber, Wu’s argument is essentially that internet service providers (ISPs) should not be able to discriminate against end-consumer preference over their networks. To poorly paraphrase, if a user wants to connect to the internet via WiFi vs. ethernet cable, or if they want to watch streaming video vs. play online games, or want to read blogs vs. email, the ISP should not be able to charge differently or throttle services based on the content of end-user activity.

It feels like a relatively milquetoast take: a consumer that pays for the internet should be able to use the service in the way that they want. But let me tell you, dear reader, that is not how major companies viewed net neutrality and it sparked a multi-decades-long fight to prevent it from coming to fruition.

Fisheries Led to Net Neutrality’s Downfall

In a weird coincidence of history, it will be a family-owned New England fishery’s objection to funding federal oversight of overfishing in the Atlantic Ocean that is the current (and potentially permanent) roadblock to net neutrality. But first - record scratch - how did we get here? (And bear with me - this is a journey and I’m not a lawyer.)

To understand the fight for (or against) net neutrality, one needs to understand the carrier classifications that the FCC uses for companies that provide telecommunication services like cable or telephone. To oversimplify, you have Title I carriers, which are essentially unregulated private companies providing telco services to consumers. And you have Tier II carriers, which are very similar to Title I except for the fact that Title II carriers can (and are) regulated by the FCC as they fall under the concept of a “common carrier.” Again, an elementary understanding of it, but one that frames the tools of the net neutrality fight fairly well.

The debate began in earnest with the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 threw ambiguity into how to classify these services, especially when it came to cable companies also acting as ISPs. The cable companies argued they should be viewed under Title I classification (which would make them unregulated by the FCC.) The FCC eventually agreed, but were challenged by non-cable company ISPs who argued that the cable company ISPs cannot be considered Title I because they has been Title II classified providers prior to the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

This fight eventually made its way to the Supreme Court in 2005 as National Cable & Telecommunications Assocation v. Brand X Internet Services, where a 6-3 court (led by Clarence Thomas) relied on what’s called the Chevron defense, which comes from a previous 1984 ruling that gave executive branch-based regulatory bodies like the FCC broad leeway in deciding what was and was not under their regulatory scope. Keep the Chevron defense in mind, as plays a crucial role in the fisheries case later on.

While BrandX was initially a loss for net neutrality supporters, it gave the FCC the power to decide if - and how - they could regulate ISPs. A few short years later, the first major fight post-BrandX began to wind its way through the courts. Comcast had been caught throttling internet bandwidth for peer-to-peer sites like BitTorrent, and the FCC demanded it stop. Comcast sued (and won), but this saw the FCC simply double down on net neutrality, putting out a list of net neutrality principles it expected ISPs - regardless of their cable company status - to follow, now dubbed the 2010 Open Internet Order. The FCC stopped just short of reclassifying them as Title II carriers, however.

Verizon didn’t like this, arguing that the FCC was overstepping their authority by telling ISPs what to do when they’re classified as Title I carriers. This set off a firestorm of discussion about whether net neutrality could ever be achieved without a Title II reclassification scheme. After vacillating between a tiered internet (which is very much anti-net neutrality) and a more open internet, the FCC eventually voted to reclassify ISPs as Title II telecommunication companies, definitively placing them under FCC regulation.

Years later, Trump came into office, had the FCC reclassify these companies as Title I, but then Biden reversed this and re-re-reclassified them as Title II carriers. Again, all of this is allowable when we take into account the Chevron defense, which allows bodies like the FCC to determine who can and cannot be regulated. The back and forth occurs like this because the FCC governing board serves at the pleasure of the president.

Now - finally - the fisheries case. Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo threw out the decades of precedence that the Chevron defense enjoyed, and the Telecommunications Act of 1996 leans towards putting ISPs under Title I classification; any ambiguity that the FCC was able to use under Chevron to ultimately decide the classification is now gone.

It is expected that Trump Part Deux will do the same thing his first administration did and allow the ISPs to be classified as Title I companies, citing the 1996 law as their reasoning. Now, the only thing that can reclassify ISPs (and maintain net neutrality) would be an act of Congress. Good luck with that any time soon.

So Now What?

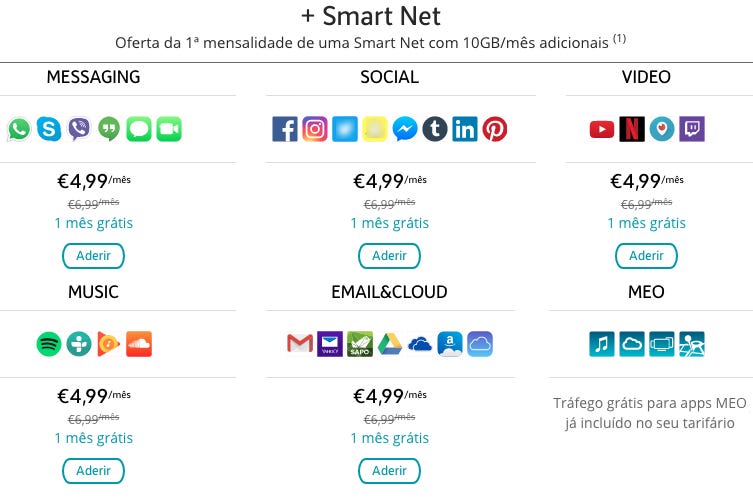

The most obvious concern when it comes to an internet that is not considered open or neutral is a tiered pricing structure based not on internet speed or even usage, but on the content being consumed by the end user. In this scenario, two consumers using the same bandwidth can be charged different prices by the same company based on the apps or services they use. This is often done under the guise of “zero rating” - allowing free sites on an internet plan along with sites you have to pay for. An example often cited is the Portuguese carrier MEO, which allows any website or app on a data plan, but allows the consumer to “zero rate” certain apps and sites to not count towards one’s data limit, effectively charging more for use of those sites and apps.

But that’s the most obvious and transparent form, and we’re talking about late-stage capitalism here. Looking at what companies have done in the past twenty years under nebulous net neutrality rules can give us a clue as to what may occur in the near future post-Loper Bright.

If I were, say, a broadband provider and I also happened be a content producer, without strong net neutrality rules I can now throttle a consumer’s connection to a rival streaming service on my internet infrastrucutre to facilitate a better user experience on my own. This would help to enable a shift of consumers to my streaming service versus others for a variety of reasons, the least of which are it is much harder to change ISPs than it is to change streaming services and in some places I am the only broadband provider in town.

This is not a hypothetical - I just described Comcast, the largest home internet service provider in the United States and the owner of streaming service Peacock (home to one of the best shows you can stream online: The Office Superfan Episodes.) They do not currently do this, nor are there any public plans to do so, but they now have the ability if they’d like, unregulated by the pesky FCC.

In another scenario, if a major ISP wants to be paid to be a preferred carrier of, say, Netflix and throttle other streaming services, a non-Chevron enabled FCC can only sit and watch. This is not an unlikely scenario, given Google’s $26 billion payouts to hardware providers to be the preferred search engine on their devices. In fact, it has precedence as Netflix was forced to pay ISPs “paid peering agreements” to ensure efficient delivery of their content across the internet. Back in 2014 they got into a public spat with Verizon when they felt they were not getting what they paid for.

So ultimately what this will do at the end of the day will drive up costs for consumers - either in the cost of streaming services you pay for (to help pay for things like paid peering agreements), or in the cost of your overall internet as they enter an unregulated space where they don’t have to worry about that annoying “public good” as common carriers. There will be no flip-flopping like there was between Trump and Biden on carrier classifications because the legal underpinning of them in Chevron no longer applies.

This newsletter takes the stance that the internet - and access to it - is a public good, warts and all. ISPs may be able to determine your internet speed and potentially your cumulative bandwidth based on a free market pricing structure, but they should not be able to determine or even influence your content preferences. Freedom is a principle this country was founded on - in name at least, even where it fell very short in practice - and an internet guided by net neutrality is integral to freedom in the 21st century.

Grab Bag Section

WTF Traffic: This Christmas season saw the family doing the NEC shuffle via car - Westchester to Boston, Boston back to Westchester, Westchester to Long Island day round trip on Christmas. I was dreading the traffic - flashbacks of sitting on the bus during college for seven and a half hours going home for the holidays from NYC to Boston, and doing the same decades later but this time with screaming children.

So we got on the road and to my surprise…nothing. A smooth ride to Boston - must be a fluke, I thought. But it was the same on the way back. And then Christmas Day - other than the dreaded Cross Island to LIE exchange, absolutely no traffic. “Perpare yourself for a disaster of a ride home,” I said to myself, hours before a preternaturally congestion-free ride back to the abode.

So I figured the first Monday after New Years would be the karmic whiplash the New York area was due after such a solid showing over the holidays. But with the advent of congestion pricing, there were noticeably fewer cars on the road in lower Manhattan and I still got a seat on the train. Is this the result of the constant doom and gloom headlines we hear about the “exodus” out of New York? The irony of people leaving New York because it feels unlivable, thus making it more livable for the people who stick around is not lost on me. Now, if we could just tackle that nagging cost of living problem.

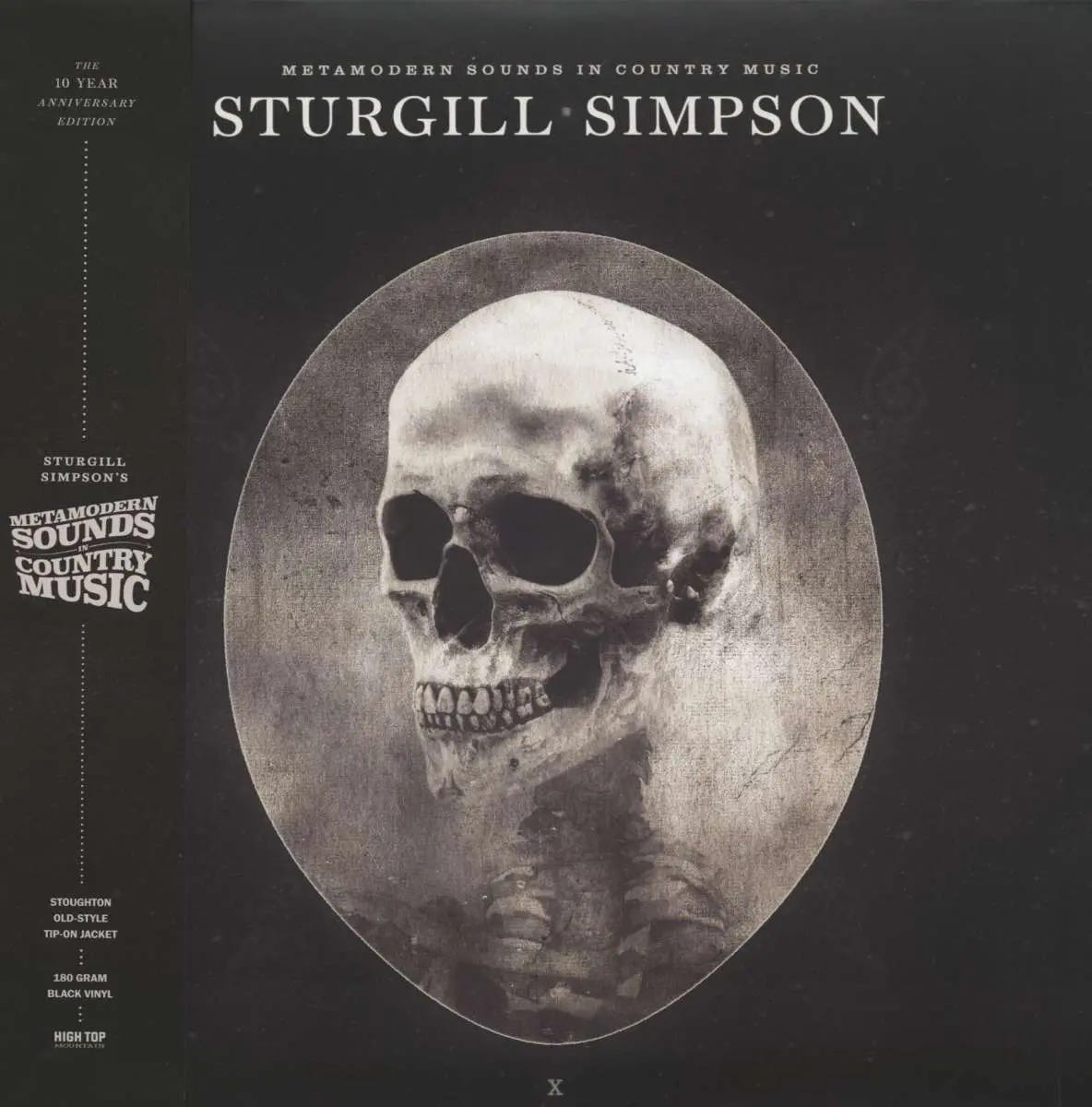

Album of the Week: I took a sneak peek at some of the survey responses, and one of them asked for some more country. Now, I am not a country guy by any means, and it could be because my default distrust of authority doesn’t seem to jive with a genre of music that in some of my most formative musical exploration years blacklisted the Dixie Chicks for criticizing George W. Bush over Iraq.

We have done some country on this newsletter in the past - we looked at George Strait’s Ocean Front Property last year. But to get more contemporary in country, the newsletter wanted someone with a rebellious streak, someone compared to “outlaw country” (and not the Archer season arc), and a self-described anarchist. So this week, we’re going to dive into Sturgill Simpson’s Metamodern Sounds in Country Music.

A nod to Ray Charles’s Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Sturgill’s album has been cited in reviews as being less “hard country” than his debut, but the intro track “Turtles All the Way Down” starts with the lines “I've seen Jesus play with flames / In a lake of fire that I was standing in.” To this newsletter, that sounds pretty country.

Honestly there’s not really any skips on the album, so trying to pinpoint the best ones is a difficult task. Songs that have stuck with me the past week are the intro track, “Life of Sin,” “The Promise,” and “Voices.” It’s little surprise that it has a solid “Universal Acclaim” tag on Metacritic and even a decade after its release it still garners Rolling Stone long reads. If you’re like this newsletter and are wading into the country scene, you could do a lot worse than this album.

Quote of the Week: “When I invented the Web, I didn't have to ask anyone's permission. Now, hundreds of millions of people are using it freely. I am worried that that is going end in the USA.” - Tim Berners-Lee

If you missed the survey last week, please take a moment - I promise it’s short!

See you next week!