When I introduced book reviews, I warned the dear readers of this newsletter that I had a genre bias and that novels would be few and far between. Then my wife told me she wanted to watch a movie with Cillian Murphy (a request I never refuse as he is an Irish hero in the arts), but that she wanted to read the book first. Fair. (As is usually the case, the book was better than the movie.)

She headed to the local library, got the book, brought it home and it turns out it hit two major criteria of mine: it was short (a mere 118 pages, including acknowledgements) and was shortlisted for The Booker Prize back in 2022 (essentially the Oscars of English language novels.) Reading it, the parallels to working today were obvious, even if depressingly so. Needless to say, there will be some spoilers.

The Plot

It’s 1985 in a small Irish town and Bill Furlong is hard at work keeping his heating business going during the busy season around Christmas. Furlong’s enterprise deals in coal and wood deliveries, as the average heating system in this part of the country at this time are ovens. Furlong squeaks by every year; he has no debts but also doesn’t have much squirreled away - a liability with a wife and five daughters.

Furlong is well-respected and a good employer - he makes sure his men are paid a fair wage and even pays for a year-end holiday party for his workers (holdco agencies, take note.) He’s a quiet man in town, not the least of which is because he comes from a single mother household where the kindness of the wealthy woman who employed his mother as a domestic gave him the opportunities he has today.

Without spoiling the entire book, Furlong stumbles upon some less-than-charitable activity being done by the local convent with respect to local unwed mothers and struggles with simply going back to his everyday life while he knows of the injustice happening in his backyard. Furlong struggles with it until the climax of the novella.

Furlong’s Emotional Journey

Even before Furlong stumbled upon the inhumanity that he did, he was in a woeful state of mind:

What was it all for? Furlong wondered. The work and the constant worry. Getting up in the dark and going to the yard, making the deliveries, one after another, the whole day long, the coming home in the dark and trying to wash the black off himself and sitting into a dinner at the table and falling asleep before waking in the dark to meet a version of the same thing, yet again. Might things never change or develop into something else, or new?

Who among us hasn’t wrestled with this feeling, particularly at times of high stress or mere lack of motivation? Get up, go to work, do the same things for your 9-5 (likely longer if you’re an exempt employee), decide what to have for dinner (somehow insanely exhausting), disassociate with a streaming offering (White Lotus S3 was legit), go to sleep, and get up to do it all again the next day. Run errands and do chores on the weekend to gear up for another week in the salt mines.

This is the existential question Furlong is struggling when he stumbles upon the horrors of a local Magdalene laundry, run by the same convent that educates his own daughters. He muses to his wife about it later that evening, who urges him to forget about it and dismisses the parallel between their own daughters the girls essentially enslaved in the convent. In a low blow, she even points out that his own mother was a “fallen woman” and isn’t it nice that her employer played the role of the convent for her.

Needless to say, this doesn’t help Furlong and despite other townspeople urging him to drop it, he continues to wrestle with what to do - if anything - and how any actions (regardless of where they fall on the spectrum of morality) will affect both his and his family’s stature in town.

Yesterday and Today

The parallels of Furlong’s moral misgivings in 1980s Ireland - both historical and contemporary - could not be more conspicuous. After the Allied liberation of German-held territory in WWII, German citizens were made to watch footage from the camps and those who were on the ground liberating camps found any excuses that locals didn’t know what was happening to be specious at best.

On American shores, Boston’s Catholic Archdiocese had so many priests as serial molesters that the paper trail alone of letters between high-ranking Catholic leaders - not to mention the outrage of local families whose children were victims of these priests - meant the knowledge of what was being covered up was widespread. Yet it took a Boston Globe special assignment years to make it public, and it opened a Pandora’s box of unconscionable sexual abuse by the Church across the US and the world.

And so it was with the Magdalene laundries. It happened behind closed doors, but conspiracies as large as these require not only a large number of doers but an even larger number of people willing to look the other way, even if they still whisper about it outside of mixed company.

But it’s harder to ignore once you’ve seen it first hand, as Bill Furlong learned. And these days the whispers and the rumors are replaced by live-streamed death and destruction in 4K right to our devices. The plausible deniability previous generations hid behind no longer exists as we see children handcuffed by ICE, medics murdered and buried in mass graves, and Seig Heil salutes on a daily basis in between the minute dopamine hits from the rest of social our feeds.

This makes the line between conspirator and enabler that much blurrier. In a world where we simply thumb through the kinds of atrocities that sparked world wars in the past, where do we fall on the spectrum of convent sister abusing “fallen women” on one side and Bill Furlong on the other?

In the novella, when the publican tells Furlong to drop the whole matter, as the Church is simply too powerful, he responds with a poignant question about the town’s complicity in the matter: “Surely they’ve only as much power as we give them, Mrs. Kehoe?”

How much power do we give the evil in this world on a daily basis, knowingly or unknowingly? Mrs. Kehoe demured at Furlong’s question, giving him a look that suggested he was more of a “foolish boy” than anything else. Given Furlong’s later actions, this world needs more foolish boys guided by the likes of Furlong’s conscious if we want to not only get through this unique moment in history, but to do so emerging better on the other side.

Book Grab Bag Section

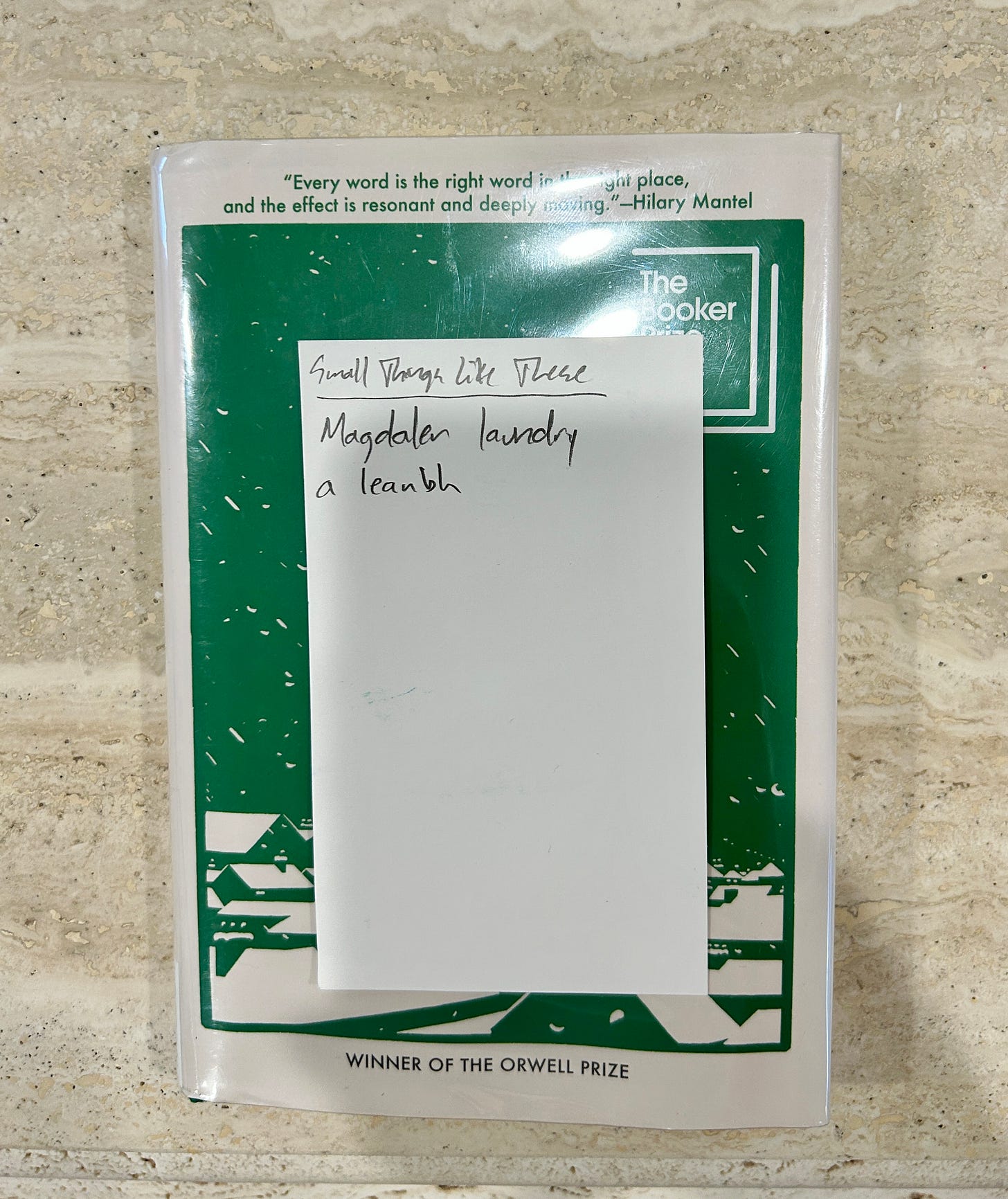

The Notecard

Magdalene Laundry - Like a lot of things imported by the British to Ireland, the Magdalene laundries were not good for the Emerald Isle. The charitable aspect of the laundries - started in the mid-18th century as a way to help reform “fallen women” (i.e. prostitutes and other undesirables at the time) - quickly gave way to exploitation and abuse. It went on for centuries, until 1993 when an unmarked grave with over 150 women was discovered by a developer and the whole thing became impossible to ignore.

a leanbh - An Irish term of endearment pronounced ah LAN-uv, meaning “little one” or “babe.” Furlong called his daughters this throughout the book and the endearment came through the page.

Quotes

“When he reached the yard gate and found the padlock seized with frost, he felt the strain of being alive and wished he had stayed in bed, but he made himself carry on and crossed to a neighbor’s house, whose light was on.” - Something about the phrase “the strain of being alive” simply popped out.

“As they carried on along and met more people Furlong did and did not know, he found himself asking was there any point in being alive without helping one another? Was it possible to carry on along through all the years, the decades, through an entire life, without once being brave enough to go against what was there and yet call yourself a Christian, and face yourself in the mirror?” - This passage itself - beautiful in and of itself - may be the climax of the book and the apex of Furlong’s journey

See you next week!

So well said - this book quietly devastates me with every reread.